December 29, 2014 at 12:32 am

December 29, 2014 at 12:32 am

The Merlin engine has so many different variants that it’s quite confusing to try and look at a comprehensive list of them all. I was wondering if anyone happened to be knowledgeable on the type, or perhaps they might recommend a good source of information. For starters, I’m curious about HP ratings. I realize that the amount of power an engine produces has a multitude of factors involved, but what are the “official” numbers for the Merlin III as fitted in the Hurricane Mk.I? I’ve seen 1,030-hp, and 1,310-hp (for WEP). Are these the correct numbers or am I off the mark?

By: Graham Boak - 6th January 2015 at 11:25

Yes, it would be the same engine in the Lancaster Mk.I and the Hurricane Mk.II, and indeed in the Halifax Mk.II. Check also Beaufighter and Wellington. With the Hercules, the Merlin XX was intended to become the RAF’s standard engine, mass produced by Ford. However there were problems fitting it to the Spitfire, requiring too much disruption of the production line, so there it was overtaken by the single speed Merlin 35.

By: Oily Rag - 5th January 2015 at 20:50

Merlin II.

[ATTACH=CONFIG]234356[/ATTACH][ATTACH=CONFIG]234356[/ATTACH]

By: PhantomII - 5th January 2015 at 20:23

Wasn’t the XX used in the Lancaster as well? Would it have been the same as the one fitted in the Hurricane II?

By: Bradburger - 2nd January 2015 at 22:53

So what is the general consensus on the Merlin XX as fitted in the Hurricane II series? How does it compare with the Merlin variants fitted in the Canadian Hurricanes? (Merlin 28 or 29?) The most common numbers are 1,280-hp for the XX and 1,300-hp for the 28/29. Any idea what fuel these figures were attained with? Are those maximum for those particular engines?

These power ratings were with 100 octane fuel.

I have detailed power ratings for the XX somewhere.

Just need to find them!

Cheers

Paul

By: PhantomII - 2nd January 2015 at 22:09

Merlin XX?

By: Camlobe - 2nd January 2015 at 12:26

Antoni,

One of the clearest and most comprehensive explanations of the differences of ‘Octane ratings’ I think I have ever read.

Camlobe

By: PhantomII - 2nd January 2015 at 11:01

Some outstanding contributions to this thread!

So what is the general consensus on the Merlin XX as fitted in the Hurricane II series? How does it compare with the Merlin variants fitted in the Canadian Hurricanes? (Merlin 28 or 29?) The most common numbers are 1,280-hp for the XX and 1,300-hp for the 28/29. Any idea what fuel these figures were attained with? Are those maximum for those particular engines?

By: minimans - 2nd January 2015 at 01:23

With a supercharger, the boost obtained is a function of the throttle opening, the throttle usually being positioned before the impeller, the boost control limits the maximum opening to the set boost pressure, at sea level this may be, say, 50% throttle, the boost control allowing the throttle to gradually open and let more air in as the ambient pressure drops with altitude, until the full throttle height is reached.

No compressed air is wasted in this way because the more you close the throttle, the less work the blower has to do, just like a vacuum cleaner motor speeding up when you cover the inlet.The reason two speeds are employed is because engines work at maximum efficiency with no throttle to restrict the air intake, so at lower altitudes, a lower speed blower runs with a greater throttle opening, plus of course, turning the impeller more slowly will use less energy, because the drive ratios are high, in the region of 6 to 9 times the crankshaft.

Pete

Thanks Pete!! thats the most clear explanation of boost control I’ve ever read for a layman to understand……………

By: MerlinPete - 1st January 2015 at 23:42

I wonder how the boost pressure is actually controlled since the gear ratio (or ratios) of the supercharger is fixed; seems a bit wasteful to just bleed-off over-pressure with some form of ‘waste-gate’ after you’ve absorbed so much power to produce that pressure in the first place!

With a supercharger, the boost obtained is a function of the throttle opening, the throttle usually being positioned before the impeller, the boost control limits the maximum opening to the set boost pressure, at sea level this may be, say, 50% throttle, the boost control allowing the throttle to gradually open and let more air in as the ambient pressure drops with altitude, until the full throttle height is reached.

No compressed air is wasted in this way because the more you close the throttle, the less work the blower has to do, just like a vacuum cleaner motor speeding up when you cover the inlet.

The reason two speeds are employed is because engines work at maximum efficiency with no throttle to restrict the air intake, so at lower altitudes, a lower speed blower runs with a greater throttle opening, plus of course, turning the impeller more slowly will use less energy, because the drive ratios are high, in the region of 6 to 9 times the crankshaft.

Pete

By: Creaking Door - 31st December 2014 at 18:46

That is interesting; I’d always assumed (wrongly it seems) that German aero-engines were typically larger in capacity but were far more moderately supercharged because of the lower octane rating of the fuels available to them.

By: antoni - 31st December 2014 at 18:06

If you think about it there are dire warning stencils at the fuel-filling points on the Bf109 for 87 octane fuel; why would they bother with these if filling it with lower octane road fuel did no harm?

You cannot compare the octane ratings of automotive gasolines with aviation gasolines, octane ratings used in the UK, Europe and Australia and most other countries in the world with those used in the USA, Canada, Brazil, and you cannot compare the octane rating quoted for German wartime aviation fuels with those quoted by the Allies because they are all different, measured under different conditions.

The octane rating of petrol is measured in a test engine and is defined by comparison with a mixture of 2,2,4-trimethylpentane (iso-octane) and n-heptane that would have the same anti-knocking capacity as the fuel under test: the percentage, by volume, of 2,2,4-trimethylpentane in that mixture is the octane number of the fuel. For example, petrol with the same knocking characteristics as a mixture of 90% iso-octane and 10% heptane would have an octane rating of 90. A rating of 90 does not mean that the petrol contains just iso-octane and heptane in these proportions, but that it has the same detonation resistance properties. Because some fuels are more knock-resistant than iso-octane, the definition has been extended to allow for octane numbers greater than 100.

In 1926 Graham Edgar suggested using these two hydrocarbons because they could produced in sufficient purity and quantity and they both have similar boiling points, thus the varying ratios should not exhibit large differences in volatility that could affect the rating test. N-heptane was already obtainable in sufficient purity from the distillation of Jeffrey pine oil. 2,2,4-trimethyl pentane was synthesised and today is usually called iso-octane. Iso-octane is a highly branched alkane (parafin) and branched alkanes burn better than chain alkanes. Iso-octane is given an octane rating of 100 and n-heptane zero.

Automotive fuel octane ratings are determined in a special single-cylinder engine with a variable compression ratio ( CR 4:1 to 18:1 ) known as a Cooperative Fuels Research ( CFR ) engine. The cylinder bore is 82.5mm, the stroke is 114.3mm, giving a displacement of 612 cm3. The piston has four compression rings, and one oil control ring. The intake valve is shrouded. The head and cylinder are one piece, and can be moved up and down to obtain the desired compression ratio. The engines have a special four-bowl carburettor that can adjust individual bowl air/fuel ratios. This facilitates rapid switching between reference fuels and samples. A magnetorestrictive detonation sensor in the combustion chamber measures the rapid changes in combustion chamber pressure caused by knock, and the amplified signal is measured on a “knockmeter” with a 0-100 scale. Only one company manufactures these engines, the Waukesha Engine Division of Dresser Industries, Waukesha. WI 53186.

Modern automotive fuels have two octane ratings, measured under different conditions. In this country, if you look at the octane ratings on the petrol pumps you will see “RON” next to them. RON is the Research Octane Number. The petrol also has another, very important, octane rating called “MON”. MON is the Motor Octane Number. During the late 1930s – mid 1960s, the RON became the important rating because it more closely represented the octane requirements of the motorist using the fuels/vehicles/roads then available. In the late 1960s German car manufacturers discovered their engines were destroying themselves on long Autobahn runs, even though the RON was within specification. They discovered that either the MON or the Sensitivity also had to be specified. The Sensitivity of a fuel is the difference between RON and MON. Because the two test methods use different test conditions, especially the intake mixture temperatures and engine speeds, then a fuel that is sensitive to changes in operating conditions will have a larger difference between the two rating methods. Modern fuels typically have sensitivities around 8 to 10. Today it is accepted that no one octane rating covers all use.

The Research (RON) method settings represent typical mild driving, without consistent heavy loads on the engine.

Test Engine conditions for Research Octane are:

Test Method ASTM D2699-92 [67]

Engine Cooperative Fuels Research ( CFR )

Engine RPM 600 RPM

Intake air temperature Varies with barometric pressure (e.g. 88kPa = 19.4C, 101.6kPa = 52.2C )

Intake air humidity 3.56 – 7.12 g H2O / kg dry air

Intake mixture temperature Not specified

Coolant temperature 100 C

Oil Temperature 57 C

Ignition Advance – fixed 13 degrees BTDC

Carburettor Venturi Set according to engine altitude (e.g. 0-500m=14.3mm, 500-1000m=15.1mm )

The conditions of the Motor method (MON) represent severe, sustained high speed, high load driving. For most hydrocarbon fuels, including those with either lead or oxygenates, the motor octane number (MON) will be lower than the research octane number (RON).

Test Engine conditions for Motor Octane are:

Test Method ASTM D2700-92 [66]

Engine Cooperative Fuels Research ( CFR )

Engine RPM 900 RPM

Intake air temperature 38 C

Intake air humidity 3.56 – 7.12 g H2O / kg dry air

Intake mixture temperature 149 C

Coolant temperature 100 C

Oil Temperature 57 C

Ignition Advance – variable Varies with compression ratio(e.g., 14 – 26 degrees BTDC)

Carburettor Venturi 14.3 mm

There is a third octane rating, called Observed Road Octane Number (RdON). It is derived from testing gasolines in real world multi-cylinder engines, normally at wide open throttle. It was developed in the 1920s and is still reliable today. The original testing was done in cars on the road but as technology developed the testing was moved to chassis dynamometers with environmental controls to improve consistency.

Visitors to the USA from Europe note that the octane ratings on petrol pumps are lower than those available in Europe. This is not an indication that they use lower octane fuels in the USA. In the USA you may see the symbol (R+M/2)on petrol pumps. (R+M/2) is the Anti Knock Index (AKI) and is the average of the RON + MON of the fuel. It is sometimes called the Pump Octane Number (PON).

AKI is used in the USA, Canada, Brazil and a few other countries and takes into account the fuel sensitivity. In 1994, there were increasing concerns in Europe about the high Sensitivity of some commercially available unleaded fuels. If the octane is distributed differently throughout the boiling range of a fuel, then engines can knock on one brand but not another brand. This “octane distribution” is especially important when sudden changes in load occur, such as high load, full throttle, acceleration. The fuel can segregate in the manifold, with the very volatile fraction reaching the combustion chamber first and, if that fraction is deficient in octane, then knock will occur until the less volatile, higher octane fractions arrive. With AKI high sensitivity will reduce the octane rating. The US 87 (RON+MON/2) unleaded gasoline is required to have a MON of 82+, thus preventing very high sensitivity fuels.

Aviation gasoline used in piston aircraft common in general aviation have slightly different methods of measuring the octane of the fuel. Aviation gasolines were all highly leaded and graded using two numbers, with common grades being 80/87, 100/130, and 115/145. The first number is the Aviation rating also called the Lean Mixture rating, and the second number is the Supercharge rating also called Rich Mixture rating. In the 1970s a new grade, 100LL (low lead = 0.53mlTEL/L instead of 1.06mlTEL/L) was introduced to replace the 80/87 and 100/130. Soon after the introduction, there was a spate of plug fouling, and high cylinder head temperatures resulting in cracked cylinder heads. The old 80/87 grade was reintroduced on a limited scale. 100LL has an aviation lean rating of 100 octane, and an aviation rich rating of 130.

The Aviation rating is determined using the automotive Motor Octane test procedure, and then corrected to an Aviation number using a table in the method – it’s usually only 1 – 2 Octane units different to the Motor value up to 100, but varies significantly above that e.g. 110 MON = 128 AN.

The second Avgas number is the Rich Mixture method Performance Number (PN – they are not commonly called octane numbers when they are above 100 ), and is determined on a supercharged version of the CFR engine which has a fixed compression ratio. The method determines the dependence of the highest permissible power (in terms of indicated mean effective pressure) on mixture strength and boost for a specific light knocking setting. The Performance Number indicates the maximum knock free power obtainable from a fuel compared to iso-octane = 100. Thus, a PN = 150 indicates that an engine designed to utilise the fuel can obtain 150% of the knock limited power of iso-octane at the same mixture ratio. This is an arbitrary scale based on iso-octane + varying amounts of TEL, derived from a survey of engines performed decades ago. Aviation gasoline PNs are rated using variations of mixture strength to obtain the maximum knock limited power in a supercharged engine. This can be extended to provide mixture response curves which define the maximum boost (rich – about 11:1 stoichiometry) and minimum boost (weak about 16:1 stoichiometry) before knock.

A common piece of claptrap promulgated by people that have no understanding of octane ratings and petrochemistry is that the Germans were forced to use low-octane rated fuels based on a very common misinterpretation about wartime fuel octane numbers.

A common British aviation fuel of the later part of the war was 100/125. The misinterpretation that German fuels have a lower octane number (and thus a poorer quality) arises because the Germans quoted the lean mix octane number for their fuels while the Allies quoted the rich mix number for their fuels. Standard German high-grade aviation fuel used in the later part of the war (given the designation C3) had lean/rich octane numbers of 100/130. The Germans would list this as a 100 octane fuel while the Allies would list it as 130 octane.

After the war the US Navy sent a Technical Mission to Germany to interview German petrochemists and examine German fuel quality, their report entitled “Technical Report 145-45 Manufacture of Aviation Gasoline in Germany” chemically analysed the different fuels and concluded “Toward the end of the war the quality of fuel being used by the German fighter planes was quite similar to that being used by the Allies”.

By: Creaking Door - 31st December 2014 at 16:24

I wonder how the boost pressure is actually controlled since the gear ratio (or ratios) of the supercharger is fixed; seems a bit wasteful to just bleed-off over-pressure with some form of ‘waste-gate’ after you’ve absorbed so much power to produce that pressure in the first place!

By: Graham Boak - 31st December 2014 at 14:12

Boost is not a fixed factor set on the ground: it is possible to run the Merlin, as with many engines of the time, with different amounts of boost, under the control of the pilot. The higher boosts are only available with higher octane fuel to avoid knocking, and I suspect the early Merlins would not withstand the boost level seen on the later variants that could utilise the 130/150 octane fuels used in the anti-V1 campaign. There are booklets available from the RR Heritage Trust that provide this kind of detail as part of the Merlin development history, but some of the information can be seen in post 3 above.

By: MerlinPete - 31st December 2014 at 14:12

Dead right, the Merlin has a servo boost control which has authority over throttle position. Merlins could run at +6.25 psi on 87 octane or 12 psi on 100 octane, giving the two different power ratings.

Spitfire “N-17” ran a Merlin II with +27 psi boost in 1939, on special fuel.

Pete

By: Creaking Door - 31st December 2014 at 13:10

Surely you can’t run engines designed for 100 octane fuel on 87 octane fuel, not without doing them some harm anyway; it isn’t just a question of lowering their performance.

What 100 octane (or 130 octane) fuel allows you to do is to run engines with a higher compression-ratio (and that is a designed-in factor; it is 6:1 for all Merlin engines) and a higher compression-pressure, which is mainly a factor of the supercharger. I’m not sure how easily controllable the compression-pressure (or ‘boost’) is on a Merlin engine but presumably it is possible to limit the compression-pressure, and therefore the performance, of the engine? But does this mean a semi-permanent adjustment to the engine on the ground?

If you think about it there are dire warning stencils at the fuel-filling points on the Bf109 for 87 octane fuel; why would they bother with these if filling it with lower octane road fuel did no harm?

By: Graham Boak - 31st December 2014 at 10:37

I suspect the museum/educational value of having Merlins spread over a large number of sites is much greater than concentrating them on one site for the benefit of a few enthusiasts.

The Germans would have been unlikely to notice any such change, as they did not meet the Spitfire until Dunkirk, after the March date quoted, and had little contact with Hurricanes before May.

The octane difference is worth remembering when considering low opinions of the Hurricane (and Spitfire) expressed by the Finns and Russians, without access to stores of 100 octane. The P-39 units of the VVS had an dedicated supply line of additives to produce 100 octane for their use, but nothing of the kind seems to have been provided for British types..

By: WZ862 - 30th December 2014 at 20:01

British Lead Additive Production

I suspect that the lower rating was the published pre-war figure and one would not advertise a massive engine improvement subsequently to one’s enemies.

As others have written the Battle of Britain was nearly completely won with US lead additive but the following may be of interest.

The following are my notes made about the Associated Octel plant Northwich and are based on commemorative history produced by the company “Making the magic bullet: a history of Northwich Works 1939-1986”

“During the 1920’s General Motors and Standard Oil (Esso) jointly developed anti-knock petrol additives through the Ethyl Gas Corporation. These compounds fractionally delay ignition of petrol/air mixtures in car and aircraft engines, allowing the engine to compress the mixture more, making the power levels higher. Britain first imported these compounds in 1928 and then throughout the 1930’s but with war looming decided that the RAF needed higher compression engines. From 1936 the Air Ministry worked with the joint partnership of the Associated Ethyl Company (importers) and ICI (manufacturers ) and eventually placed orders to build the Northwich site.

Two alkyl lead compounds, tetraethyl lead (TEL) or tetramethyl lead (TML), are used as antiknock gasoline additives. Only TEL was produced during the war. Lead alkyl is produced in autoclaves by the reaction of sodium/lead alloy with an excess of either ethyl (for TEL) or methyl (for TML) chloride in the presence of an acetone catalyst.

The first batch of TEL was produced in September 1940. Until then, the RAF fuel had been treated with imported TEL. The workforce was all drawn from ICI Winnington and Lostock, and was largely self-taught in controlling this new process.”

The 1930’s imports allowed Rolls Royce to deliver the power required for the Schneider Trophy power plants, and design engines with the required metallurgy to handle that power. The Merlin therefore had the TEL technology built in from the start.”

I cannot find my copy of Stephen Bungay’s book on the Battle of Britain but I think he may have some German reaction to this British advance. If anyone has any knowledge of the German pilot reactions to meeting Spitfires and Hurricanes suddenly performing better after the increase in octane rating from 87 to 100 it would be interesting to learn of them.

McKinstry Spitfire Portrait of a Legend p356 quotes F/L Ponsford as flying a Spitfire XIV (Griffon) with 150 octane fuel and IIRC the Sea Fury Centaurus is 130 octane rated, so development continued to the war’s end and beyond, with interesting other options including water and methanol injection to increase power output.

WZ862

By: PhantomII - 30th December 2014 at 18:46

Any ideas on why the 1,030-hp rating for the Merlin III seems to be the most commonly sourced number when reading about aircraft fitted with that engine? It would appear that both the Spit I & Hurricane I (along with the Defiant) were more powerful than I had previously thought.

By: Bradburger - 29th December 2014 at 20:48

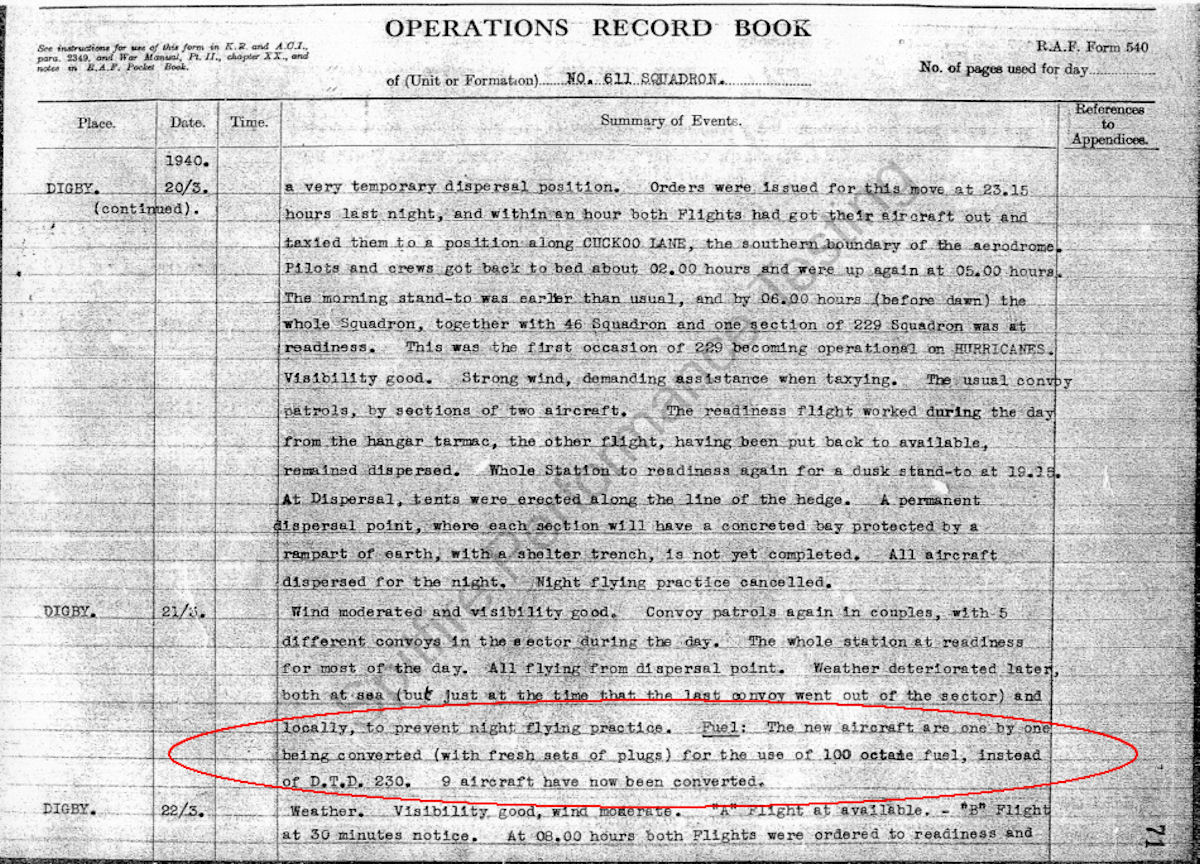

I would seem 100 octane fuel was in use operationally by the RAF in March 1940, as can be seen from this copy of a page from the 611 Sqn ORB: –

More info on 100 Octane fuel and the original source of the ORB can be found at http://www.spitfireperformance.com/spitfire-I.html

(Scroll down to the very bottom of the page).

Cheers

Paul

By: Ant.H - 29th December 2014 at 20:19

I could be completely wrong, and I can’t quote any sources off the top of my head, but I’ve always understood that 100 octane was US supplied and that there was a clause in the pre-war contract that stipulated the suspension of supplies should Britain go to war. The supply duly stopped in September ’39 and a new wartime contract had to be negotiated, 100 octane becoming available again during the latter stages of the Battle of France.