December 8, 2008 at 8:26 pm

December 8, 2008 at 8:26 pm

This is probably not the most appropriate place to post this but I don’t know where else it should go. It might get more views in Historic but there is no aviation content so I’ll leave it here.

This is something I’ve become entangled in over the last two weeks. It started off just as an exercise to see how much I could find out, little knowing I would find this piece of research so compelling. It’s lengthy but I make no excuses for that. If it’s interesting to you I think you will find it worth following through to the end. Due to the length I’ll probably post it in three or four parts.

Private William Howard Birch, Australian Imperial Force.

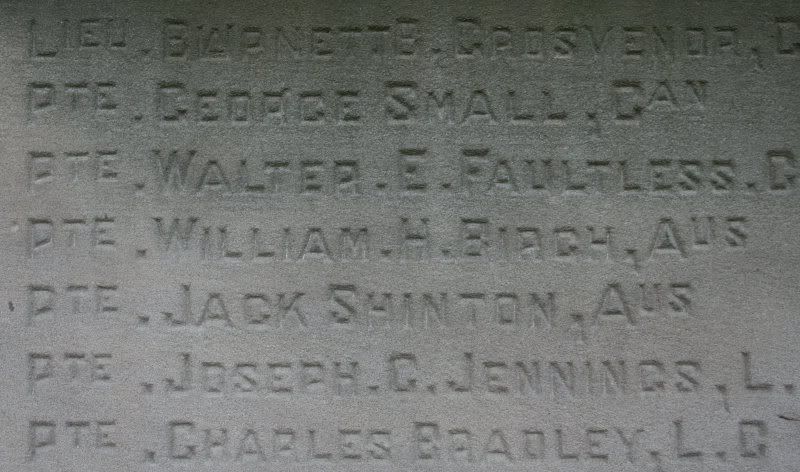

The name has been there, alongside almost 200 others, since the dedication of the Memorial some time in the 1920’s. My Dad took me to it when I was a child. We often stopped there on our way from Town. We played around it when I was in the Church Choir. We walked to it every year from school, on the Friday before Remembrance Sunday. We stood and stared at the Memorial every Remembrance Sunday and shared the sombre silence before singing a hymn. The Day Thou Gavest Lord Has Ended sticks in my mind. Foggy November mornings, a few old men in their Sunday best, medals worn proudly for a couple of hours before returning to the dark dresser drawer for another year, or maybe forever.

Over the 47 years of my lifetime, the area has changed dramatically. The old men are all gone now, maybe to join the friends they lost in those four bitter years of war. They say that no family was left untouched by the Great War and it is not hard to believe this when my own Street of 100 late Victorian terraced houses saw ten of its inhabitants killed, their names forever inscribed in stone no more than a hundred yards from their homes. Two pairs of brothers are included in that total. There is no way of knowing how many inhabitants of the Street, or even the Parish and Town, served.

All of those named have a story. A story worth telling and remembering, but few of those stories are known. The majority of those stories will remain unknown and untold. Some are easier than others to uncover, but not so easy in the telling. Of four known Swinnerton brothers, one died in a training accident, two were killed in action, the youngest of these just sixteen. The remaining brother was awarded the DCM for rescuing an Officer under fire and succumbed to his wounds shortly after the war ended. Privates Leonard Martin and Abel Jones lived a few streets apart but enlisted into the 9th Battalion, Royal Welsh Fusiliers together. They were given consecutive Service Numbers and died together on the 29th May 1915. Even in death they remain together, both commemorated on the Loos Memorial.

John McCrae, in the poem In Flanders Fields wrote:

“We are the Dead. Short days ago

We lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow,

Loved and were loved, and now we lie

In Flanders fields.”

The distance of time makes it easy to forget that the names on Memorials such as the one at the bottom of my street actually belonged to real people. Some of the names inscribed there are familiar to me from my school days. I went to school with the Grandsons and Granddaughters of these men, with their Great nephews and nieces. Familiar names of neighbours and family friends. Some of them I now realise were the brothers and children of those named on the Memorial.

Over the years I looked more closely at some of the names and the abbreviations of the Regiments in which they served. SS (South Staffordshire. The County Regiment.), RWF (Royal Welsh Fusiliers), KOYLI (King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry), I became familiar with them all, but AIF remained a mystery. Somewhere over the years I learned that AIF stood for Australian Imperial Forces. That left the question of why someone who served with the AIF would be remembered on a Memorial at the Parish Church of St. Andrew here in the Birchills district of Walsall. Before I became more competent in my research and the methods and resources available I just assumed he was a Walsall man attached, in some capacity, to the Australian Army. In a way that’s exactly what he was. But how he came to be attached to the AIF and his Service therein is, in my opinion, a story worth the telling.

It is ingrained in us from early childhood that all stories start at the beginning. This one, like so many stories of the Great War, began at the end, with a name inscribed on a Memorial. The story lies in the twenty eight years between 1890 and 1917.

William Howard Birch was born in 1890, the son of James and Elizabeth Birch. He was recorded as Howard on the 1891 Census and it seems that that is how he was always known. The family lived at the Fountain Inn at Bott Lane in the Paddock area of Walsall. The Fountain was one of a number of taverns and ale houses in the area which basically operated inside an ordinary house. Some were merely off licenses (without the license) which sold beer and spirits from the back door. In 1891, Howard had a sister Flora who was ten. Her name was actually Hannah Flora. This reveals one of the problems with Census enumerators of the period. They only wrote down what they were told. There was also a sister Lottie, seven and a brother, John, aged five.

By 1901 the family had moved just around the corner to another tavern, the Walsall House, in Bank Street. It appears likely that this house was operated along the same lines as The Fountain. Both of these taverns were demolished by, at the very latest, 1928. Licensing law was tightened and many of these back street taverns were closed as a result. By 1901, there were also two additional family members, Lillie aged nine and Bertie aged five. James and Elizabeth, Howard’s parents, were now forty four and forty two years old respectively.

Howard attended Tantarra Street School and would have left at around the age of fourteen. It is known that at some time around 1904/5 Howard became apprenticed to a firm of Painters and Decorators. This was a family firm, F. Davis, of 52 Ablewell Street, Walsall. This would have been ideal for Howard as their address was literally just around the corner from the Walsall House. The firm of F.A. Davis remained in existence until recently when it was absorbed by a Company which operates decorating contractors nationwide. Sadly, the family of F.A. Davis gave up their interest in the business some time ago.

In November 1911, Howard made a momentous decision. He was to leave Walsall and emigrate to Australia. It is believed he made the journey with another young man whose identity remains unknown. Howard settled in the Surry Hills area of Sydney and possibly lived in Holt Street. Correspondence to the Army from a Miss Ida Hateley of 11, Holt Street may yet prove to be significant.

By the summer of 1914 war was approaching. In fact it had been labeled the Great War even before it started. Walsall lost around 2,000 men in the Great War and the Walsall Territorial Battalion of the South Staffs marched out before the war was two weeks old. By this time Howard’s mother, Elizabeth, appears to have died and her husband, James, was temporarily out of the pub business and living at No 12 Cairns Street just two streets from where I sit now. No 12 was a back to back house and I have vague memories of playing there as a child. The house is now long gone and the new build houses in Cairns Street start at No 14. It was at this time that Howard’s youngest brother, Bertie, enlisted in the Royal Berkshire Regiment. It is believed he was living in West Bromwich at the time and working for a Company called Stone.

Like so many of his generation, it was inevitable that Howard would serve in some capacity and on the 29th June 1915, Howard traveled to the Liverpool Army Camp, not too far from Sydney and was enlisted into the 9th Reinforcements of the 1st Battalion Australian Imperial Forces. Howard, and all those who enlisted with him, swore an oath to…..

Well and truly serve our Sovereign Lord the King in the Australian Imperial Force from 1st July 1915 until the end of the War, and a further period of four months thereafter unless sooner discharged, dismissed, or removed therefrom; and that I will resist His Majesty’s enemies and cause His Majesty’s peace to be kept and maintained; and that I will in all matters appertaining to my service, faithfully discharge my duty according to law. SO HELP ME, GOD.

Howard’s Attestation Paper was countersigned by a Captain Harold Morrison and he was given the service Number 2787. He is described as being five feet six and a quarter inches tall and weighing 156 pounds. His complexion is described as dark with brown eyes and dark brown hair. His Religion is described variously as Church of England and Wesleyan. It was at Liverpool, New South Wales, that Howard underwent his basic Infantry training. Just three months later, on the 30th September 1915, Howard and the 9th Reinforcements traveled back to Sydney to board His Majesty’s Australian Transport A8 Argyllshire. Their destination was the First Australian Imperial Force Training Centre at Tel-El-Kebir in Egypt. This was a tented city some six miles in length which eventually provided a home for some 40,000 Australian troops.

It is not known when the Argyllshire arrived in Egypt. But when it did arrive, the men of the 9th Reinforcements joined the 1st Battalion at Tel-El-Kebir. The 1st Battalion was made up almost entirely of men who had fought at Gallipoli and following the collapse of the campaign in the Dardanelles, they had been withdrawn to Egypt in December 1915. It was expected they would have to face a combined operation by the German and Turkish forces to take control of the Suez Canal.

To be continued…..

By: Flightpath - 9th December 2008 at 22:20

Nice one Kev!!

Not generally known is that around 10% of the population of Australia had joined up and that the ANZAC corps had the highest loss rate of all allied forces during WW1.

Like most towns in britain, Australian & NZ towns all have their memorials, most nameing families that lost more than one member.

My dad had five uncles in France & Belgium (three had fought at Gallipoli), all were wounded (three wounded twice, one gassed). Here’s one of them (top left) with british, canadian, french and aussie friends………….

I often think of those young men and what they put up with.

cheers,

-John

LEST WE FORGET

By: Moggy C - 9th December 2008 at 16:30

Fantastic work, Sir. A very moving story.

Thanks for sharing your research – Ever thought of producing a book?

Don

You should know we do not allow advertising on here so Kev can’t possibly post any commercial links. 😡

http://www.amazon.co.uk/Wise-without-Eyes-Kevin-Mears/dp/0954995902/ref=sr_1_2?ie=UTF8&s=books&qid=1228840134&sr=8-2

Moggy

By: critter592 - 9th December 2008 at 15:42

Fantastic work, Sir. A very moving story.

Thanks for sharing your research – Ever thought of producing a book?

Don

By: Grey Area - 9th December 2008 at 07:28

Thanks for the kind comments, it is appreciated. However, any hat doffing should be reserved for Private Birch and his fellows. I merely had the privelige and Honour of uncovering and telling the tale, not only for Howard but for all who served.

Characteristic modesty, Kev.

This yet another example of the tireless and unpaid work that you do to ensure that that we do not forget those who gave their lives the sake of future generations, and it is both admirable and humbling to witness.

Kudos to you, Sir.

By: kev35 - 9th December 2008 at 00:43

Thanks for the kind comments, it is appreciated. However, any hat doffing should be reserved for Private Birch and his fellows. I merely had the privelige and Honour of uncovering and telling the tale, not only for Howard but for all who served. It is ever more humbling as you look at the lives behind the names. You are, to an extent, putting flesh on the bones. Sitting here on a frosty December night, warm, fed, a little drop of something warming to hand and no real prospect that I may not survive the night, it can be nothing but humbling to tell such stories. A man dead for 91 years, has, through this process, come alive before my eyes. And I am richer for having learned so much of him.

Regards,

kev35

By: Last Lightning - 9th December 2008 at 00:07

One of the most moving stories i`ve ever had the privilege of reading.

Hat also doffed

By: Moggy C - 8th December 2008 at 23:09

Doffs hat in admiration.

Both to Pvt Birch and to Kev.

Sincere thanks for your work, and for posting it.

Moggy

By: kev35 - 8th December 2008 at 20:29

On the 11th of September, Howard was moved again to No1 Australian Auxiliary Hospital at Harefield in Middlesex. Harefield Park was a house owned by the Billyard-Leake family, Australians resident in England. In November 1914 they offered the property to the Australian Government for use as a convalescent hospital. It was expected to house 60 patients in Winter and 150 in Summer. By War’s end the hospital was greatly expanded and housing as many as 1,000 patients at a time. It was here that Howard would have received the convalescent care and therapy required to equip him for return to active service or for repatriation to Australia should he have been declared unfit for further service. Howard remained at Harefield for approximately seven weeks.

The 28th of October saw Howard reporting for duty at No1 Command Depot, Perham Downs. This was a holding establishment and it was from here that troops were returned to their units, redeployed to other specialities or awaited new drafts returning to France. On the 30th October, Howard was granted fourteen days leave. It is not known where that leave was spent but I suspect it would either be with his father in Nethercote or back with friends and family in Walsall.

Two days after returning from leave, Howard was on the move again. This time it was to the 14th Training Battalion at Hurdcott. Howard stayed with this unit for just over a month undergoing training to ensure he was fit enough to return to France and to become familiar with any new weapons available to the Infantryman and any new tactics. His time in England was drawing to a close and on the 21st December 1916 Howard was at Folkstone to board the Princess Clementine. This seems to have been an overnight crossing as on the following day Howard arrived at the 5th Australian Division Base Depot, Etaples. Universally pronounced Eat Apples by the troops, Etaples was familiar to the majority of troops returning to France. After two weeks at Etaples, Howard was one of 23 other ranks who marched in to reinforce the Battalion at Flesselles. Just short of six months after he was wounded, Howard was back among the Australians. I suspect there were few if any familiar faces there to greet him upon his return.

While Howard was in hospital the Battalion had continued to occupy the trenches in the Fromelles sector for a further two months and since then had maintained a presence in the Somme Valley. Howard had returned to the freezing reality of Winter on the Somme. The intense cold was enough to contend with, but conditions in the trenches must have been appalling. Repeated cycles of freezing and thawing ensured there was never the slightest comfort. Warmer spells induced a thaw which turned the trenches into muddy rivers. Men disappeared forever into the mud. The only possible benefit being that the soft, muddy ground limited the effects of shellfire. The corollary to that was a freeze which turned the mud to concrete and increased the possibility of injury during shelling due to great chunks of frozen earth being thrown into the air. It was during this period that the Battalion earned itself a nickname. Intense cold and immersion of the feet in muddy water led to the possibility if Trench Foot. The skin of the feet would lose circulation and become fish belly white. In many cases the skin would mascerate and fall from the feet in layers or even chunks. A preventative measure was to rub whale oil into the feet to act as a protective layer against the wet. However, the Battalion CO, Lieutenant Colonel Croshaw, discovered that a layer of whale oil rubbed onto the steel helmets gave them a more presentable appearance while on parade. Because of this the Battalion became known as the “Whale Oil Guards.” Every infantryman on the Western Front knew the relentless grind of periods in the trenches, long hours in the firing line, working parties to repair and maintain trenches and the endless fatigue parties bringing supplies to the Front Line. Things were not that much better when out of the line either. Regular working parties were required even then. Aside from the fear and tension which must have pervaded almost every waking moment, it is easy to forget the bone weary exhaustion they must have felt. Not surprisingly, the combination of fatigue and the appalling conditions in which they lived, rendered them susceptible to all manner of debilitating illnesses.

Howard proved to be no exception. On the 19th April 1917, Howard was admitted to the 3rd Australian Field Ambulance and transferred the same day to the 56th Casualty Clearing Station. Howard was admitted and diagnosed with Trench Fever. This is a debilitating condition caused by the ingestion through the skin of the excreta of the louse. Characterised by a period of high fever coupled with lethargy and intense leg pains for a period of four to five days, the sufferer often began to recover well and then suffer one or more relapses. In some cases, the cycle of recovery and relapse could go on for months. Howard remained at the 56th CCS for ten days, being discharged to duty and rejoining the Battalion on the 29th of April.

The Battalion faced heavy shelling again throughout the middle of May but casualties were light. The spell of hot weather caused the war Diarist to comment on the “terrible stench” caused by the large number of unburied dead laying out in the sun. The Battalion made several more moves interspersed with periods in the trenches. Howard was sent to the Divisional Rest Camp for 16 days from the end of May and into June before rejoining the Battalion on the 12th. Life must have continued much as before for the Battalion. September saw the Battalion moving further north to the Chateau Segard and Halfway House sectors. Howard was now in Belgium.

On the night of the 24th/25th September 1917, the Battalion had moved forward to Halfway House in preparation to support an attack. It was here, whilst engaged on working parties, that the Battalion came under enemy shellfire and suffered an unknown number of casualties. Throughout the period of the 22nd to the 30th September, three Officers and 63 other ranks were killed. 2787 Private William Howard Birch, 53rd Infantry Battalion, Australian Imperial Force, was among them.

Howard’s personal effects, a fountain pen, Testament, 2 wallets, a mirror, badge, cards and photos were eventually returned to his Father James. It appears that Howard was first buried in Irish Farm Cemetery in the village of St. Jean but was later exhumed and reinterred in the much larger New Irish Farm Cemetery, an Englishman wearing the uniform of Australia and resting forever under Belgian soil.

I admit to wondering what became of Miss Ida Hateley of 11 Holt Street, Surry Hills. She wrote to letters at least to the Australian Authorities asking for more specific details of Howard’s death. The romantic in me can only assume that they were sweethearts. Did she ever marry?

For James, it must have been heartbreaking. At the time of Howard’s death, Bertie was in hospital in South Wales having been wounded for a third time. I believe he survived the war. Over the following three to four years James would have received from the Australian Government the momentoes of war his son died to earn. The 1914-15 Star Trio, known as Pip, Squeak and Wilfred. The Memorial Plaque which became known to everyone as the death penny because of its resemblance to an English penny. There would have been an illuminated Memorial Scroll as well. An opportunity would have been given to James to acquire a photograph of his son’s grave.

Howard is commemorated in a number of places. His grave near Ypres, on a panel at the Australian War Memorial, on one of many plaques in Walsall’s Town Hall, on the Memorial at the bottom of my street.

It has been both a pleasure and a privilege to come to know Howard through this research. His story is just one among so many. Indeed, he is not the only man commemorated on that Memorial to have died with the Australians. They are not the only two in Walsall either. Preliminary research indicates eighteen Walsall men died with the Australians. Several more died with Canadian units.

I wonder what their stories are?

Regards,

kev35

By: kev35 - 8th December 2008 at 20:28

The 19th of July 1916 was to see the Battalion go on the offensive for the first time in what was to become known as the Battle of Fromelles. At 1100 the Battalion were still in their positions in the trenches and a heavy bombardment on the German Front Line and communications trenches was opened. The Enemy quickly responded in kind and by 1500 the Battalion had suffered around 50 casualties. At 1600 the 54th Battalion returned to the trenches allowing the 53rd to revert to holding their original 300 yards of the Front Line with their right flank against the River Laies. A and B Companies were in the Front Line trenches with C and D Companies in the support trenches. Here they waited until 1743. The War Diary records the following…..

1743. Battn moved to attack in four waves. Half Coys A and B in first and second waves, half Coys C and D in third and fourth waves. Bn. HQ in fourth wave. First wave moved out from our trench at 5.43pm followed at a distance of 100 yds by second wave, lay down near German wire till 6pm then charged followed by third and fourth waves (C and D Coys.) Took German first and second line trenches and pushed parties about 200 yds further on to hold back enemy’s bombers who were counterattacking on front and right flank, while the remainder proceeded to consolidate the position in the German 1st/2nd line. Touch was obtained with the 54th Bn on our left but no-one could be found on our right. The line was held throughout night against violent attacks, until orders were received (about 9am) from OC 14th Bde to retire from position…(unreadable.) Our right flank being in the air the enemy had already turned it and reestablished themselves in their 1st line trenches in rear of our right. About 0930 retired though with very heavy loss. Covered by fire from our own Front Line.

For Howard, the Battle was not to last that long. As the 53rd Battalion stood up on front of the German wire and advanced they were raked by machine gun fire causing heavy casualties. Among those who died in the first moments of the Battle were Battalion’s Commanding Officer, Lieutenant Colonel I B Norris. I suspect Howard was wounded very early in the Battle, being admitted first to the 8th Australian Field Ambulance on the evening of the 19th of July. He had received gunshot wounds to both thighs which were classified as severe and had also received a gunshot wound to the ring finger of his left hand. Here he would be assessed and given immediate first aid before being moved further to the rear. Later in the evening of the 19th, as his comrades struggled to hold the positions they had taken at such cost, Howard was admitted to the 1st Australian Casualty Clearing Station. This was the first large scale medical facility that Howard would have visited. I strongly suspect that the CCS would have been overwhelmed by the number of casualties from the Battle of Fromelles. It was here that those fit enough to be returned to duty were sent back to the lines, others would have been evacuated to other hospitals nearer the coast. Those that remained were men who required immediate surgery or were considered too ill to travel to one of the Base hospitals. Howard’s wounds were serious enough for him to remain at the CCS until the 22nd from where he was taken on the ambulance train to the 2nd Canadian Stationary Hospital at Outreau near Boulogne. Howard’s journey back to England was underway but not under the circumstances he would have liked.

But what of Howard’s comrades in the 53rd? They were one of a handful of units to achieve any measure of success but as has been shown, that success could neither be maintained nor exploited. At 4.30pm on the 23rd of July 1916, the remainder of the Battalion marched back into billets at Bac St. Maur. The Battalion staff, cooks, clerks and orderlies were there to meet the Battalion. As the remaining five Officers and 170 other ranks marched in those there to greet them may well have mistaken them for a Company rather than a Battalion. The War Diary records that of 28 Officers and 823 other ranks who went into action on the evening of the 19th, 5 Officers and 30 other ranks were known to have been killed, 10 Officers and 343 other ranks were wounded and 8 Officers and 228 other ranks were listed as missing. The whole operation, which was diversionary in nature, was a complete disaster. The Bavarian Infantry Regiments facing the Australians suffered less than 1,000 casualties while the 5th Australian Division suffered over 5,000 casualties making it impossible for the Division to undertake offensive operations for many months to come.

Howard’s stay in France was nearly over for on the 24th he was taken aboard the Hospital Ship St. David and left Boulogne for England. The next day, Howard was admitted to Northamptonshire War Hospital at Dunston on the outskirts of Northampton. This was previously in use as the Northamptonshire County Asylum. At some point since his admission to the CCs it became necessary for surgeons to amputate the ring finger of Howard’s left hand at the second joint. It seems likely that Howard’s stay at Dunston followed debridement and possible surgery on the wounds to his thighs. He was to remain at Dunston until the 11th September 1916. Interestingly, Howards Service Records show that his Father James had again changed his address to the Bungalow, Nethercote, Northamptonshire. Nethercote and Dunston were approximately six miles apart. Could it be that James had moved to Nethercote to be nearer his son whilst in hospital at Dunston?

Local newspapers during the Great War often carried details of those who had been killed or wounded in the service of their Country. Walsall was no exception the Walsall Observer for the 19th August had a full page spread of photographs of some of those from the town who had been killed or wounded. Across the top of the page ran the quote from Horace – It is sweet and Honourable to die for one’s Country. And there was a photograph of Howard. Poor and grainy but at last a face was put to the name. A short sidebar gave details of his wounds, his employment and his emigration to Australia. Incredibly, on the same page was a photograph of L/Cpl Bert Birch! He had been reported as wounded in the leg and arm. It is difficult to imagine the shock felt by James upon learning that they had both been wounded.

Lance Corporal Bert Birch.

To be continued…..

By: kev35 - 8th December 2008 at 20:27

Howard was taken onto the strength of the 1st Infantry Battalion, Australian Imperial Force on the 1st of January 1916. However, his service with this unit was to be short lived. Following the withdrawal of ANZAC troops from Gallipoli, the arrival of reinforcements from Australia and a steady increase in numbers training in Australia, it was realized that there were now sufficient troops available to increase the Australian commitment from two to five Divisions. This became known as the doubling of the Army. In effect, all the Battalions were split equally in half, the division being equal between Officers, NCOs and other ranks. In this way, the 1st Battalion now had a sister Battalion, the 53rd. Once the 1st Battalion was split into the 1st and 53rd, both battalions were then made up to near full strength with reinforcements. This ensured that both Battalions had a good number of experienced Officers, NCOs and other ranks who would be able to provide help and support to the reinforcements.

Howard was transferred to the 53rd Battalion on the 13th of February 1916. The Battalion War Diary states that effectively, the Battalion came into being on the 14th of February. The move was originally greeted with little enthusiasm by the old 1st Battalion men who had fought at Gallipoli. They had lost many of their comrades and now to see their ranks further divided must have been a bitter blow. However, as with soldiers everywhere, humour and rivalry soon returned. The 53rd Battalion War Diary records the following…..

There is no doubt that the Battalion justified its existence from the commencement, as it was after only a very short time that the ex. members of the 1st Battalion were perfectly happy under the new order of things, although the few remarks bandied about between the two Battalions were nothing if not funny. The 1st were not slow in informing all and sundry that they were the “Dinkums” and the 53rd were the “War Babies”, and the two camps had sign boards to this effect all over their lines.

The complete organization of the new Battalion took some weeks and was not finalized until after the Battalion had moved to its new positions at Ferry Post. This move was made to counter the anticipated Turco-German threat to the Suez Canal. The move commenced on the 27th March. Ferry Post was located across the Suez Canal on the Sinai Peninsula. Although there was a good road between Tel-El-Kebir and Moasca, it was decided that the Battalion would travel across country. The battalion War Diarist was particularly scathing of the route taken and a few remarks from the diary describe far more eloquently than I the rigours of that match. It should also be remembered that the Battalion marched carrying all their kit, including their rifles and an extra 120 rounds of ammunition per man…..

Any members of the 14th Aust. Inf. Brigade who took part in the never-to-be-forgotten march from TEL-EL-KEBIR to FERRY’S POST will, I dare say, yet shudder at the thought of it.

The march having commenced at 8 am on the 27th initially went well. The heat was hard to endure but the ground was firm and by nightfall they were settling down for a night’s rest near Mahsana. They had covered a distance of 15 to 20 miles. The following day’s march was much more challenging. The ground became soft and unforgiving requiring more effort. It is reported that on this second day the column lost its camel train and along with it their precious reserves of water. Each man had to survive the day with only what remained in his water bottle.

The journey continued through the afternoon and after almost indescribable hardships in which Australian endurance was strained to a breaking point, Moasca was reached. No praise can be too great for the New Zealand regiments who were stationed there, for the work they did in searching the Desert, succouring those of our men who succumbed to the intense heat.

After a night’s rest, during which I suspect little rest was found, the Battalion paraded for inspection by H.R.H. the Prince of Wales. The journey to Ferry Post was completed later that afternoon.

For the next two months or so the Battalion continued training while making preparations foe any advance by Turkish forces. The Battalion was brought to full strength during this period. As the threat of a Turco-German offensive lessened, it was decided that the 53rd Battalion were now ready to go to France. Throughout early June, the Battalion moved steadily back towards Moasca in preparation for the train journey to Alexandria. It was on the 19th of June that the 32 Officers and 958 men of the 53rd Infantry Battalion, Australian Imperial Force boarded the Royal George for the voyage to France and their baptism of fire on the Western Front.

Early in the morning of the 27th of June, the Royal George docked at Marseille and the men of the 53rd Battalion disembarked and took their first steps on French soil. At 0800 the battalion entrained for Thionnes, a journey which was to take two and a half days. Frequent halts at the many small stations along the way gave opportunity for many men of the Battalion to pick up the odd word of French. Their arrival at every station and halt along the way was greeted with enthusiasm by the local population.

Back in England, with at least two of his sons serving, James had taken the decision to re-enter the licensed trade, becoming landlord of The Vine Inn, Burbury Street, Hockley in Birmingham. It appears that a pub of the same name exists in Burbury Street today. As James was now a widower and with his children all grown and gone their separate ways, I suspect James’s decision to rejoin the licensed trade was at least in part an attempt to assuage his loneliness.

As part of a Battalion of a thousand men in a Brigade of three thousand, James would never have been short of company. But he must have felt the sadness of being away from both his family in England and those friends he left behind in Sydney. Maybe there was even a sweetheart?

After a week in billets at Thionnes, at 0900 on the morning of the 8th of July, the Battalion marched out with the rest of the 14th Brigade to billets at Estaires. They moved again on the 10th to Sailly and then Fleurbaix where they moved into the trenches and took over from the 47th Battalion AIF. The relief was completed by 0210 on the 11th. It should be remembered that this was eleven days into the Battle of the Somme and that the Battalion must have heard the enormous barrage and been aware of the aftermath of the dreadful losses incurred by the Allies on the 1st of July. The War Diary describes their first six days in the trenches as easy due to the sector being quiet with not much enemy activity. I can’t help but wonder whether the men of the Battalion, Howard included, were disappointed or relieved to have missed the opening day of the Somme offensive. At 0130 on the 16th the Battalion was relieved by the 12th Battalion King’s Royal Rifles and moved to billets at Bac-St.-Maur. The relief was a short one as the Battalion was back in the trenches relieving the 57th Battalion AIF at 0300 on the 17th. At 0300 on the 18th the Battalion took over another set of trenches from the 54th Battalion AIF. This Battalion of almost one thousand men were now covering a section of trench some 600 yards long.

To be continued…..